J.D. Foster

J.D. Foster

Former Senior Vice President, Economic Policy Division, and Former Chief Economist

Published

January 30, 2018

Does the United States have a “looming student debt crisis?” And, if so, why?

You would sure think such a crisis is about to break and wash over the U.S. economy for all the media’s ominous-toned reporting. Recently, the Brookings Institution added to the din by releasing a very thorough report indicating default rates on student loan debt were higher than previously thought. To be sure, student loan debt has risen dramatically, but is it really a “crisis?”

Before we get too carried away, a review of the data is in order.

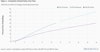

Without doubt, student loan debt has risen dramatically. To pick a year, in 2003 student loan debt stood at about $240 billion according to Federal Reserve figures, whereas by the end of 2017 the total exceeded $1.4 trillion. Increasing nearly six fold in 14 years is certainly an attention-getter, and at least suggests an economy-threatening debt bubble waiting to pop.

To be sure, for those students who took on debt, the many years of payments can really cramp one’s style. Some of this debt was taken on to acquire a great education and the former student, now gainfully employed, will pay it off without too much trouble. But a significant portion of the debt was taken on ill-advisedly, and so it should hardly surprise that default rates are troubling even as interest rates remain low.

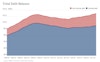

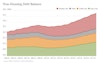

So the rise in debt is remarkable, stunning even, and for some former students a problem. Now, about that “crisis”; the first additional bit of data worth considering is total household debt, which has risen from about $7.2 trillion in 2003 to about $13 trillion in 2017. So, while student loan debt was increasing nearly six-fold, total household debt grew relatively modestly in percentage terms. In fact, as a share of disposable personal income, the total household debt burden at 90% is fairly normal for the modern era, and barely changed compared to 2003. So the student debt bubble seems little threat to the economy.

But another question quickly follows: How can student loan debt rise so rapidly while total household debt did not? Answer: Other forms of borrowing grew much more slowly. Home mortgage and home equity loans soared in the 2000s and then plummeted so by 2017 they had returned to normal levels. In contrast, total outstanding auto loans and miscellaneous sources of debt experienced little growth over the period, almost perfectly offsetting the rise in student loan debt.

In short, whatever issues arise from current and former students rapidly increasing their debt loads, the issue would seem to pose little challenge for the overall economy. For example, for every debt-burdened former student compelled to dedicate a substantial chunk of his or her income to student loan payments, somebody else in the economy is making smaller payments on an auto loan or other debt form, and usually at much lower interest rates.

If student loan default rates are concerning, this is a problem for the former students who have to find a way forward. Their plight is lamentable, but it is theirs and not a crisis.

Likewise, the lenders who must work with these debtors knew the risks going in. Default rates higher than expected may be unpleasant for the lenders, but it hardly qualifies as a crisis for the rest of us.

The shift in borrowing patterns does raise an interesting question, however. Are affected potential borrowers choosing student debt over other kinds of debt, or is the rise of student debt crowding out other borrowing? One clue is to compare prices. Even though interest rates generally are near historical lows, credit card interest rates remain in a lofty range of roughly 14% to 22%, so it’s hardly surprising borrowers have avoided credit card debt whenever possible.

What about student loans? The rate on a direct loan is currently about 4.45 percent, with about a 1% origination fee per draw. But it gets better. A graduate doesn’t have to begin making payments until after graduation and if he or she demonstrated financial need then the government pays the interest until graduation. What does it all mean? In short, it means an even lower effective interest rate than the posted rate. So it would appear that in terms of cost, student borrowers are making a pretty smart decision regarding loan type.

The federal government has made it relatively inexpensive to borrow to go to college, which is great in that a college education is now available to more people. It may be less great in that low borrowing costs may be playing a significant role in pushing up or at least facilitating the rapid rise in college costs. And it may be even less great for students who borrow to achieve degrees which cannot justify the costs economically, or even worse for those students who leave school early with a substantial debt and no diploma. These are all real issues worthy of debate.

However you slice it, the rise in student debt is a natural consequence of federal policy. The government wanted to provide cheap loans so more students could go to college. Guess what? It worked spectacularly, proving once again that prices still matter. The policy is not without painful side effects for certain individuals and lenders, but despite the pain the rise in student loan debt has not led to an unsustainable increase in household debt, so the crisis aspect of the “student debt crisis” seems significantly overblown.

About the authors

J.D. Foster

Dr. J.D. Foster is the former senior vice president, Economic Policy Division, and former chief economist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. He explores and explains developments in the U.S. and global economies.